Communication requires that participants make their messages maximally understandable in a particular context... On the other hand, communication takes place in social structures which are inevitably marked by power differences, and this affects how each participant understands the notion of "maximal understanding." Participants in positions of power can force other participants into greater efforts of interpretation.It seems that this is true in many aspects of life, visual and otherwise. An obvious example of this may be the stereotypical moody boss who barks out a vague set of orders, leaving the people working for him to guess at his exact meaning in an attempt to meet his unclear demands. Yet we can see this at play in many more subtle settings. A concept may be mentioned by a professor without extensive explanation or clarity, because the professor knows that even without an explanation, students will need to research it in order to pass an exam. My experience in technical translation has also shown me that instruction manuals for home assembly of various products (furniture, etc.) tend to be more simple and clear than those for industrial devices. Now clearly, this is due in part to the presumed expertise of the user: an industrial engineer is assumed to have a wealth of knowledge and therefore require significantly less technical explanation than a college student assembling a computer desk for the first time. Still, is it possible that there are some dynamics of power at play? If the college student is frustrated with the assembly instructions, he may simply return the desk and buy another one from a different manufacturer. However, an engineer is responsible for doing her job, and figuring out how to follow the directions in her manual, regardless of how unclear the directions may be.

Another topic that the authors bring up is how visual ideas may be represented through varying means that are significant to the artist in what they represent to him or her. The notable example given is that of a 3-year-old boy, whose drawing of a car does not highlight its shape, but rather the circular motion of its wheels (in his representation through circles). In this way, the meaning of the resulting picture may not be immediately clear to an outside observer without an explanation, but the image carries clear meaning to its creator. Because of the child's background of knowledge and associations, this set of symbols is entirely logical and meaningful. Both this book and our previous text talk about the importance of context and background knowledge in interpreting images. Reading Images mentions the fact that we may perceive artistic artifacts from other cultures as beautiful, interesting, or bizarre, but we may be incapable of understanding their meaning because we are not a part of that culture, and do not have the background information and cultural associations that allow particular symbols to represent concrete ideas.

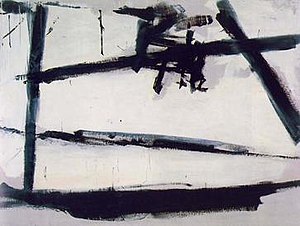

But I would like to return to the idea of visual representation through the motion of creating an image. I decided to search for examples of modern art that employ associations of motion, rather than visual associations, in making a painting.

One well-known artist who focused on motion in the creation of his paintings was Jackson Pollock. He eschewed the easel and paintbrush, and preferred unconventional tools, such as sticks, trowels, and knives, as well as dripping and splattering paint onto a canvas on the floor from all four sides.

His work was part of the Action Painting movement, which eschewed the conventional use of paintbrushes to create careful images, and instead focused on the physical act of producing the painting as an important element of the art itself. This work by Franz Kline is also a well-known example of action painting:

No comments:

Post a Comment